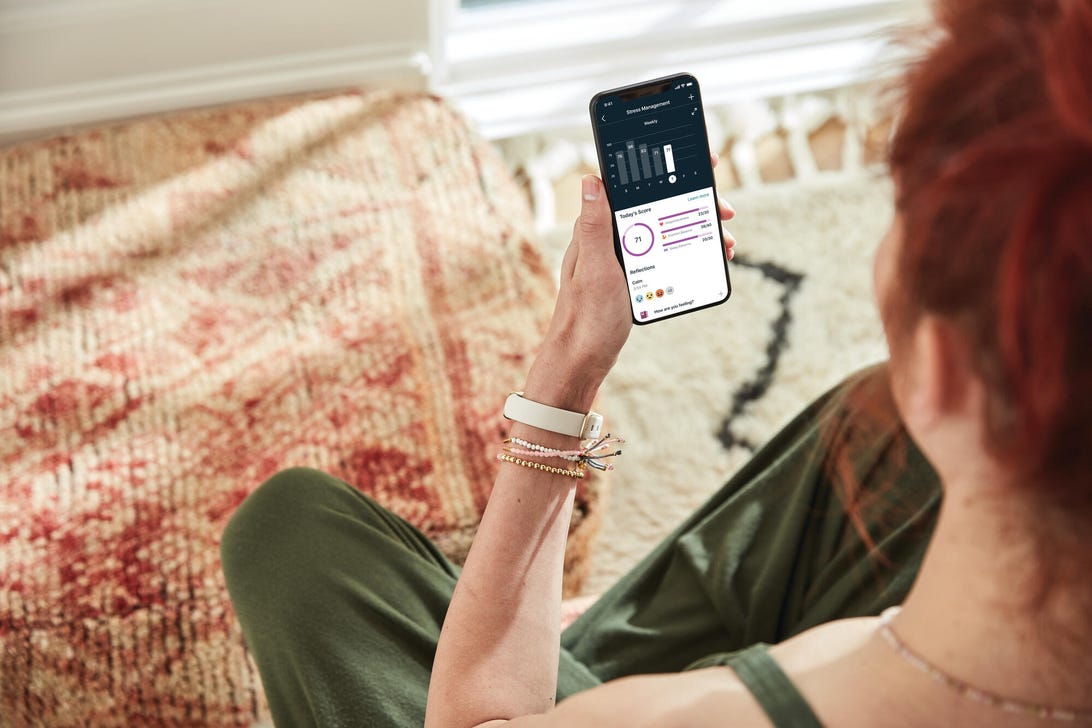

Fitbit’s latest tracker, Luxe, is one part of a bigger picture.

Fitbit

A Fitbit used to be a little gadget to count your steps. Those days are long gone: Fitbits are now continuous heart and sleep monitors, with aspirations that go even deeper. Now owned by Google, Fitbit is still creating new fitness trackers, like the new Luxe. The company’s subscription-based Fitbit Premium service continues to add new wellness routines, including celebrity guides such as Deepak Chopra.

Where do things go next? Will Fitbit ever venture off-wrist? How can these trackers possibly assist with diseases like COVID-19?

Fitbit co-founder and CTO Eric Friedman offers some insights on where Fitbit is at now, and where things are headed next.

Last year’s Fitbit Sense added EDA, ECG and temperature sensors. Some of these could make their way into smaller wearables, eventually.

Richard Peterson/CNET

Shrinking down sensors on-wrist

Fitbit plans to continue exploring more advanced sensors on its bigger watches, while letting sensor tech trickle down over time into more optimized, smaller, lower-cost bands. “Because they have a larger battery, and kind of more mass, it’s easier to try out brand new sensors in them and learn,” Friedman says of last year’s sensor-studded Fitbit Sense — which added temperature, a stress-sensing electrodermal sensor and an electrocardiogram, or ECG — compared to the much more pared-down new Fitbit Luxe, which leans mostly on its optical heart-rate sensor for things like sleep and stress measurements.

Friedman makes the comparison to where heart rate on wearables was years ago, living mainly on big watches while smaller bands just measured steps. The optical heart-rate sensor is also where the most evolution has happened, adding a lot of extra algorithm-based insights that didn’t exist before. “When we first launched heart rate in our smartwatch, it was really about a kind of workout experience,” Friedman says of where things were seven years ago. “But as things progressed, we started to be able to tease out more and more from heart rate.”

He sees heart-rate variability as an important new metric, and related to that, atrial fibrillation. Fitbit recently finished a 500,000-person AFib study, but unlike the Apple Watch, most Fitbits don’t measure estimated atrial fibrillation through the optical heart-rate sensor. For that, you’d need a Fitbit Sense with its ECG feature.

Possibilities of blood pressure

Fitbit’s watches don’t check for blood pressure yet, but the company is hoping that a measurement called pulse arrival time could eventually be the answer on wrists. Pulse arrival time, which can be measured through Fitbit’s ECG-enabled Sense watch (but isn’t available for Sense users yet), compares the electrical signal from the ECG with the blood flow measured via the optical heart-rate sensor. Friedman sees this as a possible path to estimated blood pressure measurements down the road.

“Obviously, the ideal thing is we get absolute blood pressure, but even if we get relative blood pressure and say, ‘Hey, something changed, you should go get it looked at,’ that to me would be a huge win, too,” Friedman says. “If not relative blood pressure, something around heart health. There is something there, we just need to figure that out.” He says that Fitbit’s progress on studying pulse arrival time is still in the early stages. “We’ve done stuff internally, on friends and family. And we recently launched something where we’re asking a bunch of our users to help us by collecting data, seeing how we can generate better signal, and ultimately help them by giving them additional metrics.”

There are few wearables that measure blood pressure right now, with the exception of the physically inflating Omron HeartGuide, cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration, and Samsung’s recent Galaxy Watch Active models (versions 2 and 3), which require calibration with a blood-pressure cuff. It’s a territory many companies are still trying to crack.

Google’s Nest Hub just added sleep tracking. Will it eventually intersect with Fitbit?

Chris Monroe/CNET

Ambient computing and fitness off-wrist

Fitbit’s acquisition by Google certainly points to possible integration with a lot of other products, possibly even off-wrist devices like the Nest Hub, which just added experimental sleep tracking using radar, but doesn’t hook into Fitbit.

“We’re in the very early stages of integration, there’s nothing to preannounce at the moment,” Friedman says of Fitbit’s connections to the rest of the Google ecosystem. “But we’re really excited about what Google brings to the table in terms of AI technology.”

But ambient computing, a vision of the always-connected future that is a big focus for Google lately, could factor into where Fitbit heads next. “I think ambient computing is really interesting, ambient sensing,” Friedman says. “I think there are some things that will make sense for Fitbit to bring to market, there are some things that will make sense for Google plus Fitbit to bring to market.”

Friedman sees the Fitbit mobile app as being the hub, either way. “There might be manifestations of some of that stuff on your wrist,” but that wrist-based tech is, “not the be-all and end-all.”

The Oura ring, another wellness wearable, calculates a “readiness score” that’s already been adapted for use in environments like the NBA’s 2020 bubbling. Fitbit’s exploring similar concepts.

Scott Stein/CNET

Wearables as an alert for sickness (and COVID)

Despite being more than a year into the pandemic, wearable tech hasn’t necessarily turned into the helpful wrist-indicator of illness symptoms that many had hoped for. But many companies, Fitbit included, are still working on large studies looking at the relationship between wrist metrics, like heart rate variability and temperature, on the likelihood of illness.

Finding a way to put these findings into a Fitbit software update is a bigger challenge. Friedman says, “We are able to look at things like HRV (heart rate variability), SPO2 (blood oxygen), heart rate, sleep patterns, all this stuff. We are working to bring that to market, working with the FDA on tuning the sensitivity and specificity to figure out what is the right thing based on where the disease is today.”

Friedman sees this research being a doorway to help us be aware of illness symptoms in general, similar to what already exists on devices such as the Oura ring, but he’s also worried about getting it right. “Technology is not infallible,” Friedman says. “We’re working with both the medical establishment and the FDA to figure out what is the right thing for population health.” Friedman also still sees challenges of building trust between Fitbit and its data and doctors who will make their own assessments. In health tech, it’s a delicate handoff.

Fitbit’s future could be hyperpersonalized

Friedman says that the Fitbit Sense’s electrodermal EDA sensor for stress is the sensor he remains most excited about. But over the next 10 years, he sees the Fitbit platform continuing to evolve as an increasingly customized tool.

“I think you’re going to see a lot more of the behavior-change stuff — behavior change and customization,” he says, also referring to finding ways to help people with health alerts that could possibly save their lives. “How can we be that seatbelt for them?”

Sleep tracking didn’t get interesting for Fitbit, according to Friedman, until it seemed like the information could be acted on. He notes that the pandemic has been bad for health in a lot of ways, but that sleep has actually improved, leading to lower average resting heart rate.

Finally, Friedman sees the possibility of a more customized future where coaching tools and guidance know how to treat people individually. “One of the things I underestimated when we first started Fitbit was the power of the brain,” he says of trying to find ways that people will listen to suggestions and not see them as judgmental. The approach may get increasingly different depending on who’s using the service.

“I think that’s where stuff is going to go over the next five to 10 years, that hyperpersonalization driving that behavior change. And then obviously, there’s all kinds of other things to measure, both on and off the body, that I think are really interesting.”

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.

:quality(80))